And So It Begins

- cornerstoneams

- May 5, 2025

- 7 min read

CAMS View from the Corner

May 6, 2025

A few weeks ago we offered an edition with a central perspective of Capital vs. Labor and how this old school-lingo could be used to succinctly view the current Administration’s policy of bringing back the production of goods and services to the U.S. homeland.

Underneath all of the noise, and there is a lot of noise radiating from every conceivable camp, to include said Administration, we have a Capital vs. Labor discussion, which has not been a discussion for some time – you pick the number of decades. Three-plus decades would be a starting point.

To be clear in drawing distinctions between the two, Capital refers to the owners of financial resources in a very broad sense. Drilling down to be more specific, those resources can be in corporate ownership, machinery, buildings, etc., all of which play a role in the production of goods and services.

Labor is the worker’s input via the labor they provide in producing goods and services.

Capital has been in a dominating position via outsourcing and globalization as they took advantage of labor wage rate differences of X markets around the globe to that of the United States. This essentially boiled down to a wage rate arbitrage play.

Arbitrage is executing to your advantage the difference in prices in two or more markets. It could be thought of as U.S. based Capital went short on U.S. labor and long on foreign labor as a generalized way to think of the storyline.

That is, they proceeded to “buy” the cheaper wage rates of foreign laborers to that of domestic-based laborers by setting up foreign operations on an ever larger scale, or to simply outsource to foreign producers.

Given time, X decades down the path, the trend offered foreign production of goods and services became the go-to. With this, under this Capital vs. Labor view, labor had ever less bargaining power as all knew operations could, and would be moved to X foreign locale if labor became too demanding.

With this, labor lost its voice, if you will, and essentially took whatever was offered.

The old-school days of labor essentially offering, “Meet our demands or who do you have to produce for you,” were replaced by Capital’s view of “We can source production at much cheaper levels via our foreign operations and/or foreign producers.”

With this, Capital sat in a dominating position to that of Labor as time rolled on.

Enter On-shoring Policies

The objective of bringing more production of goods and services back to the U.S. has a few buzzwords attached to it. On-shoring is one phrase that acts as a catchall to describe what we think of as an attempt to reindustrialize the homeland.

Regardless of the phrase used, the bottom line objective is to see U.S. based labor playing a larger role in the production of goods and services. This objective is essentially offering to push recent decades of history in reverse. That is, from offshore production to onshore production.

In our observation, in an attempt to reduce this very large and very noisy storyline down to some level of simplicity, it offers a non-verbalized objective to see labor regain some leverage at the Capital vs. Labor table. This offers an inherent attempt to rebalance the scales a bit between the two important camps.

These two groups are essential to one another and are necessary for economic activity, growth, productivity, and higher standards of living. There is also a long-standing division between the two whereby each one desires more of the economic pie.

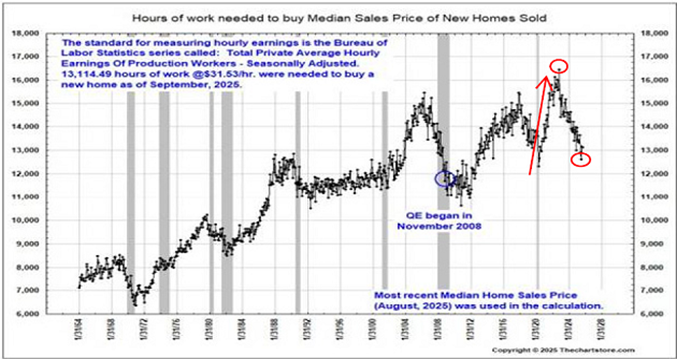

As a general description, in recent decades, Capital has been thriving while Labor has not. Capital has been getting ever more of the pie if you will.

This may change in the form of Labor ultimately receiving more compensation, more of the economic pie resulting in reduced profit margins for Capital.

Importantly, this does not mean Capital becomes unprofitable; rather, it becomes less profitable, meaning, for example, profits as a percentage of sales (using one metric to make the point) reduce in a general sense.

We cannot offer that this will be the case for every company across every industry. That is a larger story with the inherent elastic or inelastic demand nature of X companies and industries. That topic is beyond this edition’s view.

In stock market terms, this means listed companies may be, and perhaps most likely will be, less profitable, as viewed through profit margin metrics, as demand for labor increases relative to the supply of labor if tariffs produce the desired result of a tremendous increase in U.S. based production.

Revisiting our aforementioned historical mindset of Labor essentially offering to Capital, “Meet our demands or who do you have to produce for you,” may morph into, “Meet our demands or deal with increased cost of goods sold from your foreign production via tariffs.”

Capital’s inferred historical response, as offered above, went something like, “We can source production at much cheaper levels via our foreign operations and/or foreign producers,” and may simplistically morph into, “Um, hmm, point taken.”

With this, the inherent incentive to move production back to the U.S. to sidestep tariffs may be acted upon by producers. Maybe.

The Tariff Narrative – Guaranteed Price Inflation

From the get of this national tariff discussion, we’ve seen the narrative builders essentially jump right to a one-for-one relationship view. That is, X tariff increase equals a commensurate X increase in price inflation.

As offered in our edition a few weeks ago on this topic, that simple narrative leaves out important economic aspects of the relationship of producers to consumers.

Keeping this as succinct as possible, we need to remember that consumers have a choice with their consumption while producers always have competition and market share at the forefront of their minds when pricing goods and services.

To think an X increase in input costs equals guaranteed pass-through from producers to consumers, with neither entity offering a change in behavior via their own best interests, leans toward fallacy.

Producers will consider how much, if any, cost increase can be passed through without hurting themselves relative to market share via competition. Producers always consider potential consumer pushback via said consumers offering, “No thanks, we’ll pass on that price point,” with their consumption choices.

There is always a dance between the two, and this will continue even with tariffs entering the scene.

Consumers will not simply think, upon seeing X increase in price due to tariff’s, “Oh, its tariffs; we must pay, no questions asked.” Rather, they can, and will walk away from X purchase consideration with an implied message to X producer, “Eat some of this increased cost, or you do not have our business.”

This walks us full circle to producers being vigilant on their pricing to maintain market share and demand levels as best they can. If they cannot pass through all of their increased costs to consumers, they then see higher input costs relative to the price they receive at retail. This boils down to reduced profit margins.

The overall point here is there is not a guaranteed, one-for-one relationship of X increase in tariff equals X increase in consumer price inflation.

And so it Begins

Our overriding message on this entire national tariff discussion leans far more toward corporate profit margin reduction than it does toward guaranteed, one-for-one tariff-induced price inflation increases.

On a personal note, with this in mind, in recent days I had an involuntary verbalization of, “and so it begins,” upon seeing some company releases around tariffs that implicitly spoke to profit margin reductions rather than confidently believing they can pass through tariff costs. As examples, two unrelated businesses chimed in with the same theme.

Just last week, the CEO of General Motors offered in a media interview, as well as offering it is built into their Wall Street guidance, that they will not be attempting to pass on tariff-related costs to their customers. She cited fierce competition (think market share concerns) as well as a belief that there is a lot they can do to impact tariffs by continuing to increase their U.S. production beyond what they do currently.

For its part, Albertsons, the large food and drug retailer that offers a plethora of product lines, informed suppliers it will not accept cost increases related to tariffs. For their part, they informed said suppliers via a formal letter emphasizing tariff-related cost increases are subject to dispute if invoices are found to have such charges.

These are two examples, representing the pass-through of tariff costs, which speaks to profit margin reductions to X degree.

Consider, if companies en masse choose to sidestep the tariff issue via on-shoring of the production of goods and services. If, yes, at this stage we emphasize if, this were to occur, consider the increase in demand for labor relative to the supply of labor.

Under such a scenario, per our view of Capital vs. Labor, Labor’s leverage at the table would increase notably, in particular when compared to their lack thereof in recent decades. We would expect their newfound leverage, if this unfolds, to result in Labor’s increasing take from the whole of the economic pie.

Corporate profit margins, generally speaking, would be expected to reduce. This would essentially place recent decades of history in reverse, whereby Capital dominated the balance between them which resulted in ever higher levels of corporate profitability.

We will continue to share on this topic through our drilled-down view of Capital vs. Labor as time rolls on. In our minds, this will be a long-running, fascinating socioeconomic topic to observe, monitor, and share on. This very large macro topic will play through markets, as do all large macro topics, according to how it unfolds.

It is far too early to offer, with confidence, the many tributaries of consideration this will open up, as well as close down; hence our ongoing monitoring as we move forward.

I wish you well…

Ken Reinhart

Director, Market Research & Portfolio Analysis

Comments