Housing Affordability and the Stock Market

- cornerstoneams

- Dec 4, 2025

- 5 min read

Housing affordability, or the lack thereof, seemingly is a constant topic for discussion throughout society. Whether explicitly stated and discussed or simply inferred within an unrelated topic, the lack of affordable housing for the general citizenry is a topic that is often front and center.

Upon hearing this topic addressed, at times, I will simultaneously hear an impromptu dialogue within myself that offers, “If you think housing is expensive, you should look at the stock market.”

Call it an occupational hazard.

That is, when consistently sifting through many asset markets and viewing them through various angles, to include, importantly, valuation angles, the process cannot help but leave a time-stamped impression on the brain that is not easily forgotten, given enough exposure to various markets.

Housing is tangible, which allows people to intuitively understand how affordable or unaffordable that market is relative to incomes. Individuals know what their income levels are and what the cost of their desired housing costs are, which offers them a real-time measure of affordability, for themselves at least.

Add a touch of personal economic history and people can easily intuit if housing has become more or less affordable.

The stock market does not allow for such an intuitive understanding relative to its “affordability,” if you will. Individuals do not buy the stock market; they buy a share of the stock market or a share of a company that is publicly traded within the stock market.

They think in terms of overall dollars invested.

I am investing $10,000, as an example. What never follows such a decision is the question that always follows when participating in the housing market, or any consumer market. That is, okay, now tell me, what will my $10,000 buy me?

We often say that price offers little inherent information, but valuation tells all.

This is why home prices for the masses are relatively easy to assess on the affordability scale, as they know the price, but equally important, they know their income levels which is an essential ingredient in gauging affordability. Said differently and to the point of this edition, they are able to intuit a valuation level onto the home price.

Valuation takes price and places it into context.

In this case the valuation context is the income levels of the hoped-for purchasers, or renters.

As a side note, mortgage rates do not play a role here as an additional input, as we are not looking at the cost of carry. That is, the cost to carry the note for the underlying asset. Rather, our motivation is to determine a valuation level of the price of the home. Income relative to price offers a valuation context.

A Macro View

What if we took the above approach on a large macro scale rather than down to an individual storyline in order to gauge general valuation levels of two key asset markets?

Here in 2025 we have dedicated some editions to the topic of market valuations for the stock market, and we also sprinkled in a couple for the housing market, via an hour’s work measure.

When sharing how many hours of work it takes to purchase the two different markets, we noted, through that valuation metric, that on a trend growth rate basis housing was cheap when compared to stock market valuation levels. That was then; this is now.

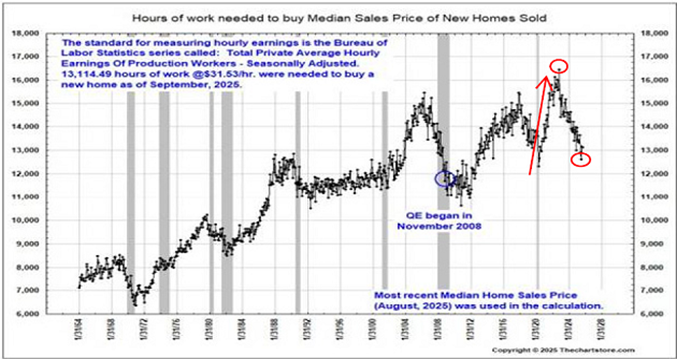

Below, we update the measures. Both date back to 1964 to the current day for historical perspective.

The top chart is how many hours of work it takes to purchase the S&P 500, while the bottom is the median sales price of new homes sold to represent the general housing market. Note the trend trajectories of each.

For the bulk of citizens, it is wages that ultimately pay for housing. The above places the growth in wages, over the decades displayed, to that of the growth in home prices, using the median sales price of new homes sold.

Back in the 1960s through the mid-1980s, it took around 8000–9000 hours of work to purchase the median price for a new home. Over ensuing decades this escalated to a high point of just over 16,000 hours. Our current reading measures in the low-13,000 hours area.

While the hours worked for the S&P 500 went up approximately 9 times over the decades displayed, housing “only” doubled. Think, 8000 hours, to the high water mark of just over 16,000 hours.

Unlike the S&P 500 chart, which continues to post higher highs in this measure, the above housing measure is off its highs and is essentially trendless, i.e., it is in a range, although it has trended lower of late.

The essence of the measure is that it is a representation of the everyday household’s general income trajectory to that of the price trend trajectory of X market. This allows for a comparison of the perspective of market prices and their historical trend to that of general income trends.

As this year has progressed, for its part, the stock market has continued to move ever higher with its valuation level relative to average hourly wages. Housing, on the other hand, has seen its valuation level move a bit lower.

With this, the stock market has continued to outpace the housing market, on a trend basis, relative to how expensive (think valuation) it is when placing it into the context of average hourly earnings.

This is not to say that housing is historically cheap via this measure.

Rather, the point is that as expensive as most feel the housing market is in the current day, when using a comparable valuation approach, the stock market continues to easily outpace, on a trend basis, the very market that most people talk about frequently as being highly priced, and/or unaffordable.

On a personal note, strangely, I don't think I've heard much shared about how unaffordable the stock market is even while its valuation levels are stratospheric. Many other valuation metrics confirm this view, some of which we have shared in 2025.

While offering this, it is important, very important, to realize that valuation measures are a terrible timing tool, which is to say, they offer next to nothing in terms of their reliable forward guidance on market direction. For that, we continue with our focus on market participants' behaviors via market-based trading and the broad economic tea leaves.

For now, with the above in mind, you have a visual depiction of what the general stock market and the general housing market look like, not in price, but in a valuation measure of how many hours of work it takes to purchase either.

I wish you well…

Ken Reinhart

Director, Market Research and Portfolio Analysis

Comments