Powell was far too Generous with his Valuation Description

- cornerstoneams

- Sep 25, 2025

- 6 min read

On Tuesday of this week, Chairman Powell of the Federal Reserve gave a speech in Warwick, Rhode Island, which was followed by questions from attendees directed to the chairman.

Cutting to the gist of this Q&A by an attendee, the chairman was asked how much emphasis the Fed places on (stock) market prices and whether the Fed has a higher tolerance for higher values.

Drilling down to the punch line, if you will, Chairman Powell offered, “But you are right, by many measures, for example, equity prices are fairly highly valued.”

We have offered occasional editions over recent years, including recent months, whereby we focused on stock market valuations. Valuation is a process of taking price and placing it into context. Price alone tells us little, but valuation informs immensely.

We always offer, and do so here today as well, that when discussing market valuations, it is imperative to appreciate their near uselessness as stock market timing tools.

At the same time, it is also imperative for a market participant at any level to have a sense of the valuation levels of any market they are participating in.

We liken it to understanding the quality of the water that a participant’s capital is swimming in. The higher the current valuation, relative to history, the lower the quality of water that a participant’s capital is swimming in.

Historically high valuation levels can become even more historically rich, as there is no magic line in the sand whereby if X valuation level is attained, it immediately offers a ringing of a bell to all participants to leave the stock market ASAP. Hence, the reason that valuation studies have a poor track record as timing tools.

What a historically highly valued stock market does offer is the fact that capital is at greater risk, generally speaking. Risk assets, such as stocks, are classified as risk assets for a reason. Simply, they can go down and go down a lot.

Obviously, at the individual company level, a stock price can go to zero if the company runs aground.

Generally, People Love High Valuation Market Environments

In a broader sense, thinking of the stock market as a whole, prices offer more risk of moving notably lower when valuation levels are historically high. When valuation levels are high, there is less room for broad economic and/or company-specific error. Said differently, perfection is priced into the stock market.

Conversely, when valuation levels are historically low for the stock market as a whole, there is less risk of collective prices moving notably lower. Stocks are cheap; there is a lot more room for error.

Interestingly, generally speaking, people at large are far more comfortable placing their capital in lower-quality water (think high-valuation stock market backdrops) than they are when the quality of said water is high, i.e., when the stock market’s valuation level is historically low.

When stock prices are richly valued, what normally comes with this is a wealth of public participation. Think, comfort in numbers. Hey, everyone is doing it; what can go wrong. All of this participation brings with it higher prices, and, oftentimes, higher valuation levels.

Historically speaking, when valuation levels are very low, and through this relative risk is low, many fear participating in the low valuation stock market backdrop out of concern prices will move lower and lower. Few people are participating, think little comfort via small numbers.

So, the higher the valuation level, the more general comfort there is among the masses to participate in the highly valued stock market.

The escalating stock prices act in a similar vein to that of a light for a moth. The attraction is mesmerizing. Those escalating stock prices are like a siren call to come get yours, lest you miss out – valuation levels be damned.

Employing logic, does this make sense?

It makes sense when thinking of our aforementioned comfort in numbers, which aligns with being all too human, realizing humans are a social species.

Comfort in numbers helps in making it make sense, viewed through the above lens, but is truly illogical when considering risk assets are most at risk when valuation levels are historically high.

And this brings us to the current day and the chairman’s response. He was being far too generous in labeling our current stock market valuation backdrop as “fairly highly valued.”

Honestly, it was surprising that he answered this at all. It is customary for Fed chiefs and Treasury officials to steer clear of stock market valuation questions so as not to upset any proverbial apple carts.

But in fairness, “fairly highly valued” could be interpreted many ways. For instance, does he mean that the stock market is highly valued but is fairly valued? We could continue, but surely the point is made – we could slice and dice the chairman’s reply in many ways. Perfect Fedspeak in its own right.

In our current stock markets’ valuation backdrop, what is not questionable, in any way, is the actual reality of our current stock market when viewing it through any valuation lens. We are epically highly valued when overlaying history onto any valuation measure used in the current day.

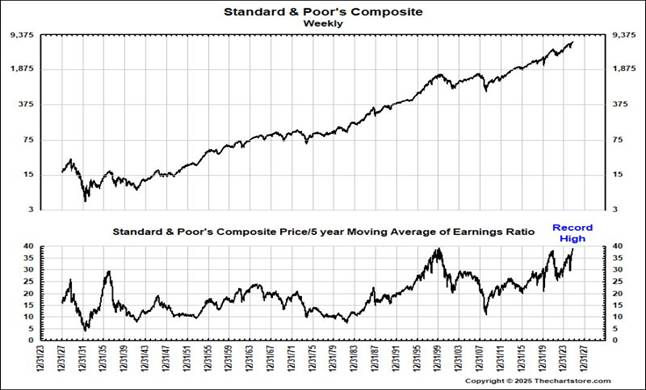

Below we will look at a stock market valuation measure to add a visual.

We offer a hat tip to Ron over at the Chart Store for today’s valuation chart.

We like history, especially when placing any stock market valuation measure into context for our current stock market environment.

The above offers a near 100-year view dating back to 1927.

In the upper pane of the above chart, we see the price along the path to the current day for the S&P 500 index. That covers price, but as shared, price alone offers little information and context.

The real information is in the lower pane, which places price into a valuation context using the underlying earnings of the companies that make up the index. Earnings are the lifeblood of companies, and, ultimately, also for their underlying stock prices.

Price is being divided by the 5-year moving average of the earnings of the companies held within the index. This is called a P/E (price-to-earnings) ratio on a 5-year rolling average.

The 5-year period is used to smooth out the bumps along the path of quarterly earnings. With this, we get context of the current S&P price relative to its 5-year average earnings.

The lower pane of the above chart speaks for itself. We are at an all-time high, on a P/E basis, think valuation basis, dating back to 1927. Think back to any time in history that may ring a bell of stock market excess.

How about the roaring 1920s with the well-known top of 1929? Relative to today’s stock market valuation levels, that was child’s play when viewing historical valuation levels.

How about the well-known stock market crash of 1987? That was not even close to today’s valuation levels.

How about the late 1990s as the dot-com bubble found its pin and imploded over the next few years? Our current stock market has also exceeded that level, albeit marginally.

The obvious point is history is speaking through a valuation lens and is offering, unequivocally, that our current stock market is epically highly valued. Prices have been bid up at a trajectory far exceeding the growth in underlying earnings. This leaves in its wake, given time, an ever-higher valuation market backdrop. We are now historic.

Importantly, very importantly, the above valuation approach is corroborated through various other valuation metrics.

For example, the CAPE ratio, which is known as the Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio, also known as the Shiller P/E ratio, whereby it uses the previous 10-year moving average of earnings, offers a similar story, which, in its case, dates back to the 1870’s.

We could continue, but the point would be redundant. This stock market is priced into the stratosphere when placing it into context via valuation measures. So, yes, Chairman Powell was truly being generous with his vague description of “fairly highly valued” when describing the stock market valuation landscape.

As laid out above, and we emphasize this, the above offers next to nothing in terms of its usefulness in stock market timing. Also as offered, it is important for any market participant to know the quality of the water their capital is swimming in, i.e., what is the valuation landscape offering.

For our part in managing assets under our care, we are immersed in awareness of the valuation landscape and fully understand how risk is high with such valuation levels. We are participating in this market landscape with eyes wide open, and when deploying capital, we do so judiciously.

In addition, we are not afraid to head for the exits while capital is deployed and seek safe harbor when signs of questionable market participant behaviors stack up. This is not marketing lingo; we really do this and are quite serious about it. Capital preservation is also part of capital management. Not every market environment is a “swing for the fences” environment.

We offer, for what it is worth, to anyone to consider a similar approach and mindset.

That comfort in numbers can prove misleading, given time. Respect the landscape, participate accordingly, and your capital will thank you.

I wish you well…

Ken Reinhart

Director, Market Research & Portfolio Analysis

Comments