Wait, what was that Housing Remark About?

- cornerstoneams

- Aug 7, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2025

In our previous edition we dipped a toe into the valuation storyline for the stock market at large. As offered in that edition, there are a plethora of ways to place price into context via valuation measurements.

Valuation simply contextualizes price in order to gauge what it means in a larger sense.

On an individual basis everyone does this with a near-robotic intuitive approach.

Let's keep it simple. Upon seeing X item of interest to the consumer in us, what follows is some form of a mental process that boils down to a question: Is the item worth the price. From there a host of additional mental processes kick in as we try to place that price into the context of value.

When the "item" is a large macroeconomic landscape type of storyline, the process is a bigger picture approach.

For the stock market, as an example, it is not about a product of a company or the company itself, but rather, how the cumulative stock market is trading in price and, from that price, what valuation context we can reach.

This process always includes history for the valuation result itself in order to gauge how the current price stands relative to the history of the valuation measure selected. This offers its own form of context - a historical context.

Is this market expensive or cheap, as offered through the lens of X valuation approach, through its own historical track record.

In our previous edition we went very big picture and brought two large pieces of the socioeconomic landscape together in order to place stock market pricing into some perspective relative to what the everyday wage earner is paid on an average hourly basis.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) computes average wages for a host of areas throughout the economic system. An often referenced average is the BLS' Total Private Average Hourly Earnings of Production Workers measure to gauge and track average wage levels and their growth rates within the broad economy.

The view here is, over time, average wages continually increase, but have those growing wages maintained their buying power of the stock market at large. Has the price of the stock market, via a major index, exceeded the growth in wages.

Taking average wages and charting over decades how many hours worked it takes to purchase said stock market index offers insight into these two large component pieces within the economic landscape.

In our previous edition we shared a 60-year chart that depicted an all-time high level of hours worked to purchase the S&P 500 index. It registered 200 hours of work to purchase the S&P 500 index when using the aforementioned BLS average hourly earnings figure in the computation.

We noted, using the chart's history as a guide, how the current number of hours worked is 10 times higher than what was the normal range dating back to the bulk of the 1970s through the mid-1980s.

With that noted, we offered an offhand comment where we stated, "And you thought the housing market trajectory has gotten out of hand relative to incomes in recent decades eh!?"

Some discussions suggested a follow-on edition on this hours worked valuation approach could be informative. This time though, with the inclusion of housing relative to the hours worked valuation approach.

With this, we will look at the excerpted one-liner from our previous edition, which infers the 10-time growth level of hours worked for the stock market in recent decades dwarfs that of the trajectory of the housing market (that is, the market, not a region, city, or neighborhood - we are doing big-picture views on this.) using hours worked for housing at large.

Below we include both charts, stacked on each other for visual purposes.

Again, we offer a hat tip to Ron over at the Chart Store for these computations and charts.

Our bottom chart also dates back 60 years for data comparison to that of the first chart, which we shared in our previous edition for the S&P 500 index. As noted and depicted in the top chart, it takes 200 hours of work to purchase the S&P. This is an all-time high in the decades displayed.

Our focus for today's edition is the second chart, directly above.

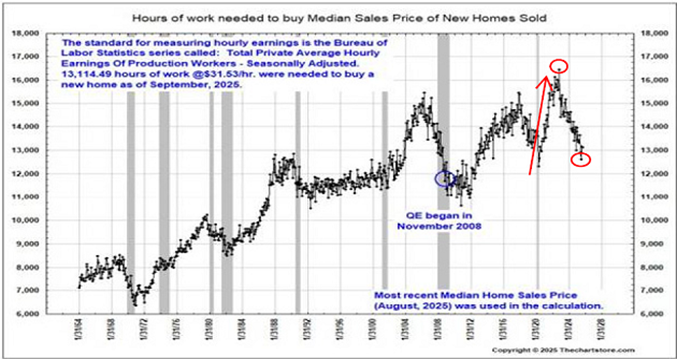

This takes the Median Sales Price of New Homes Sold and places them into the context of the BLS' Average Hourly Earnings of Production Workers earnings.

For the bulk of citizens, it is wages that ultimately pay for housing. The above places the growth in wages, over the decades displayed, to that of the growth in home prices, using the median sales price of new homes sold.

Back in the 1960s through the mid-1980s, it took around 8000-9000 hours worked to purchase the median price for a new home. Over ensuing decades this escalated to a high point of just over 16,000 hours. Our current reading measures in the mid-13,000 hours worked area.

While the hours worked for the S&P 500 went up 10 times over the decades displayed, housing "only" doubled. Think, 8000 hours, to a high level of just over 16,000 hours.

Unlike the S&P 500 chart, which continues to post higher highs in this measure, the above housing measure is off its highs and is essentially trendless, i.e., it is in a range.

The two charts together are what elicited the short comment in our previous edition, which we excerpted earlier.

To reiterate, in relation to the stock market's tenfold increase via the hours worked measure, the low-to-high point for housing doubled in its hours worked result, as shown above.

While offering this, it is important, very important, to realize that valuation measures are a terrible timing tool, which is to say, they offer next to nothing in terms of their reliable forward guidance on market direction. For that, we continue with our obsession with market participants' behaviors via market-based trading and the broad economic tea leaves.

For now, with the above in mind, you have a visual depiction of what the general stock market and the general housing market look like, not in price per se, but in a valuation measure of how many hours worked it takes to purchase either.

I wish you well....

Ken Reinhart

Director, Market Research & Portfolio Analysis

Comments